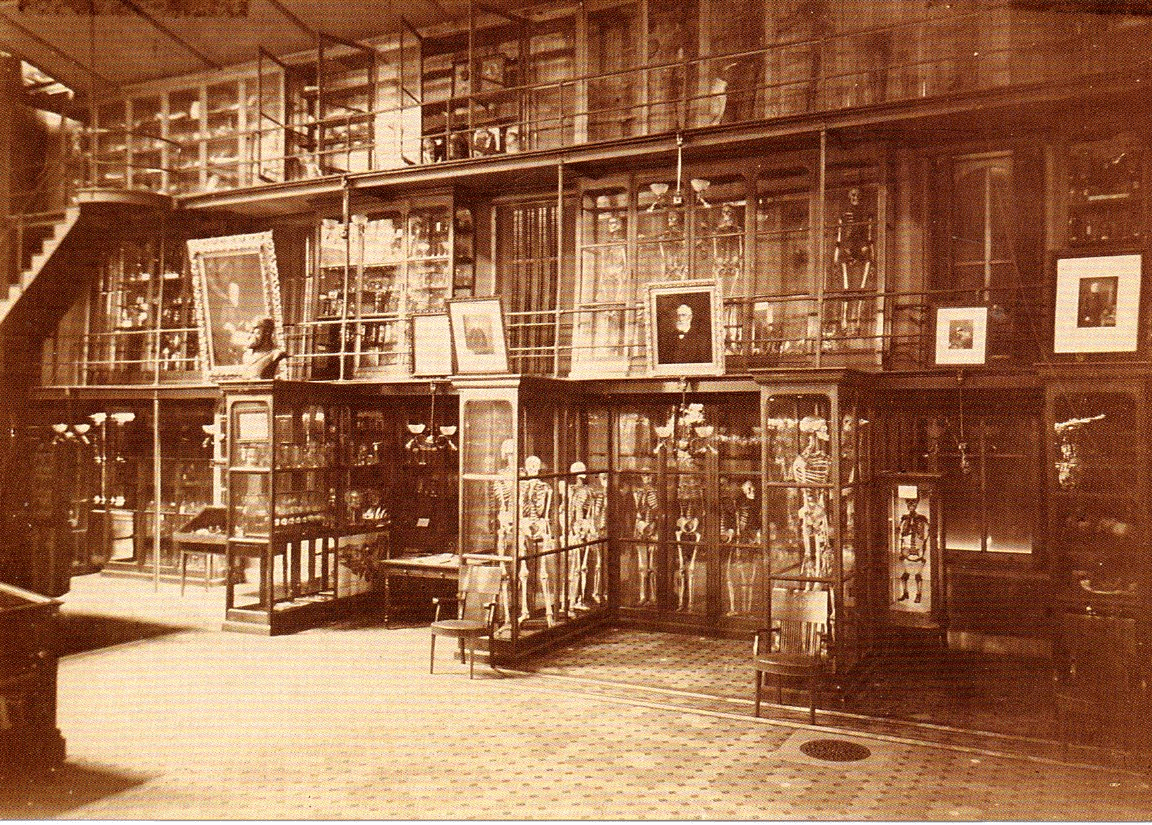

Located in the heart of Philadelphia within the College of Physicians building, the Mütter Museum is one of the world’s most renowned collections of medical artifacts, biological anomalies, and anatomical pathologies. Founded in 1858 following a generous donation from Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, the institution has evolved from a private teaching cabinet for professors into a global cultural phenomenon. It is a place where science meets art, showcasing the human body in its most unconventional yet awe-inspiring forms. More than a mere “sideshow” of oddities, the museum serves as an archive of biological diversity, helping us understand the limits of human endurance and the evolution of medicine. Join us as we explore the world of anatomy at iphiladelphia.net.

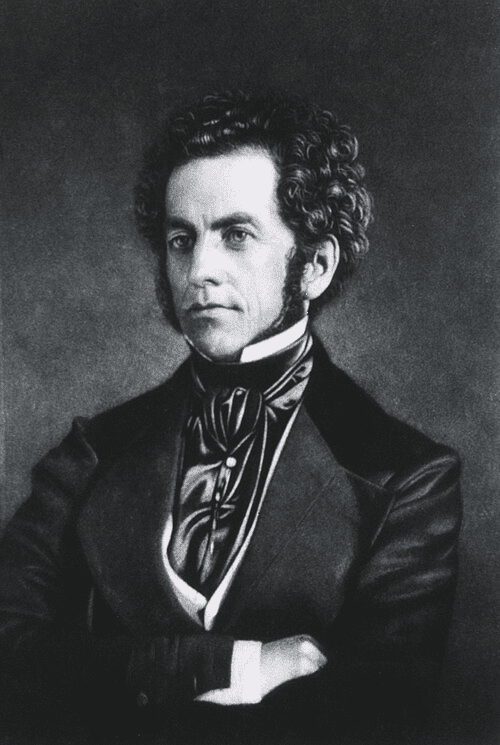

A Visionary Surgeon and His Legacy

Dr. Thomas Mütter was a pioneering 19th-century surgeon who specialized in complex reconstructive procedures for physical deformities. At a time when many doctors turned away “hopeless” cases, Mütter sought to restore his patients’ humanity. Throughout his life, he amassed a unique collection of specimens, models, and surgical tools to educate the next generation of physicians.

- The Gift. As his health began to fail, Mütter donated his private collection of over 1,700 objects to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, along with a $30,000 endowment.

- The Vision. His primary condition was the creation of a museum that would continuously expand and serve as a center for medical enlightenment.

- The Modern Institution. Today, the museum’s holdings exceed 25,000 items, including “wet” specimens, skeletons, wax models, and antique surgical equipment.

Mütter believed that observing real-world pathology was the key to understanding disease, a principle that his legacy has upheld for over 150 years.

Legendary Exhibits

The museum is famous for its “star” exhibits, each carrying a tragic or profound story. These are not just bones; they are testaments to the lives of individuals who contributed to science even after death.

- The Skeleton of Harry Eastlack. A man whose muscles and joints gradually turned into bone due to a rare genetic condition called Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP). His skeleton remains essential for modern genetic research.

- The “Kentucky Giant” Skeleton. Standing over 7’6 (2.29 m)” tall, this specimen of pathological gigantism vividly illustrates the impact of hormonal disorders on the human frame.

- The Hyrtl Skull Collection. A wall of 139 human skulls collected by Viennese anatomist Joseph Hyrtl. This collection was used to debunk phrenology—a pseudoscience that attempted to link skull shape to intelligence or character. Each skull is inscribed with its origin and cause of death.

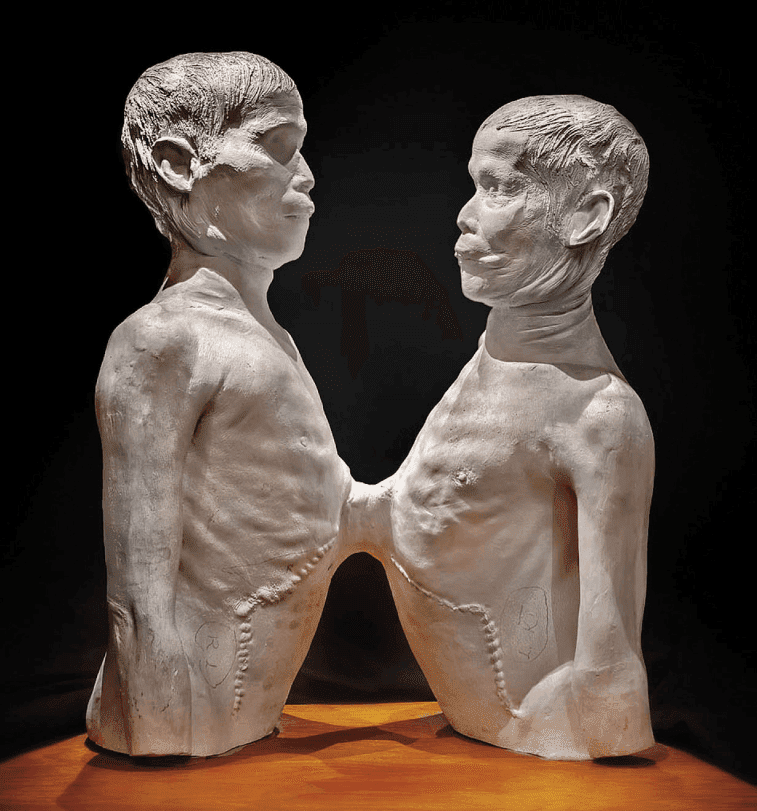

- The Cast and Conjoined Liver of Chang and Eng Bunker. The original “Siamese Twins” from whom the term originated. Connected at the chest, their shared liver, preserved in formaldehyde, demonstrates why 19th-century medicine could not safely separate them.

- President Grover Cleveland’s Secret Tumor. A piece of hidden history: in 1893, the U.S. President underwent secret surgery on a private yacht to remove a cancerous tumor from his jaw, avoiding a stock market panic. The specimen remains on display today.

- Albert Einstein’s Brain. The Mütter Museum is one of the few places on Earth where visitors can see actual fragments of the great physicist’s brain. Microscopic slides reveal the structures scientists studied to locate the source of his genius.

- The Giant Megacolon. Belonging to a circus performer known as “The Balloon Man,” this organ grew to a staggering 8 feet (2.44 m) long and weighed over 40 pounds (ca. 18 kg) due to Hirschsprung’s disease.

- The Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection. A pioneer of laryngoscopy, Dr. Jackson collected 2,374 objects he removed from patients’ airways without surgery, ranging from coins and toys to tiny watch parts.

- The Skeleton of Marie Bonnin. Suffering from severe rickets, her frame serves as a classic medical example of how a lack of sunlight and vitamins in childhood can irreversibly warp the human skeleton.

- The Corset-Deformed Skeleton. A stark reminder of how social beauty standards can physically alter the body. This skeleton shows the radical narrowing of the rib cage and internal displacement caused by years of tight-lacing, a norm during the Victorian era that significantly shortened women’s lives.

The “Soap Lady” and the Mysteries of Preservation

One of the museum’s most captivating and eerie residents is the “Soap Lady.” Exhumed in Philadelphia in 1875, her body underwent a rare process of natural mummification.

Due to the specific chemical composition of the soil and moisture at her burial site, her body fat turned into adipocere, a substance resembling hard soap. This preserved her form and facial features for decades. X-rays and CT scans have allowed researchers to study the diet and health of 19th-century Philadelphians through her remains.

A Mirror of Humanity: Why the Mütter Museum Is a Hymn to Life

A visit to the Mütter Museum is often described as a walk between fascination and awe. Yet, behind the glass cases, there is no intent to shock—only a profound manifesto of life. This collection stands as the world’s most expressive textbook on gratitude for our bodies and modern science.

Each exhibit is a silent witness to an era when medicine lacked the tools to fight infections or genetic anomalies. Today’s visitor is given a unique perspective:

- The Price of Progress. Conditions that were once an inevitable death sentence are now successfully treated or prevented through early intervention.

- The Fragility of Balance. The museum vividly demonstrates the complexity of our organisms and the vital importance of maintaining our health.

- Redefining Standards. Seeing how fashion once dictated anatomy (such as corset-warped skeletons) prompts us to reflect on how our current habits shape our future selves.

Ultimately, the Mütter Museum is not about death; it is about human resilience and the titanic efforts of generations of Philadelphia physicians. It reminds us that health is not merely the absence of pain, but a profound gift and the result of a thousand-year struggle for knowledge.

Leaving these halls, you don’t just close a chapter of medical history—you begin to appreciate every breath, every movement, and every capability of a body protected by modern medicine.