During the 18th and 19th centuries, Philadelphia evolved into a true “Rome for Physicians,” where the line between rigorous scientific research and public performance was almost nonexistent. At a time when most people viewed the inner workings of the human body as a sacred mystery, Philadelphia’s anatomists transformed dissections into captivating lectures that drew not only medical students but also the curious social elite. It was an era where understanding the flesh required not just a sharp scalpel, but a flair for the dramatic. To learn more about this peculiar historical tradition, visit iphiladelphia.net.

Anatomical Theaters: The Architecture of Discovery

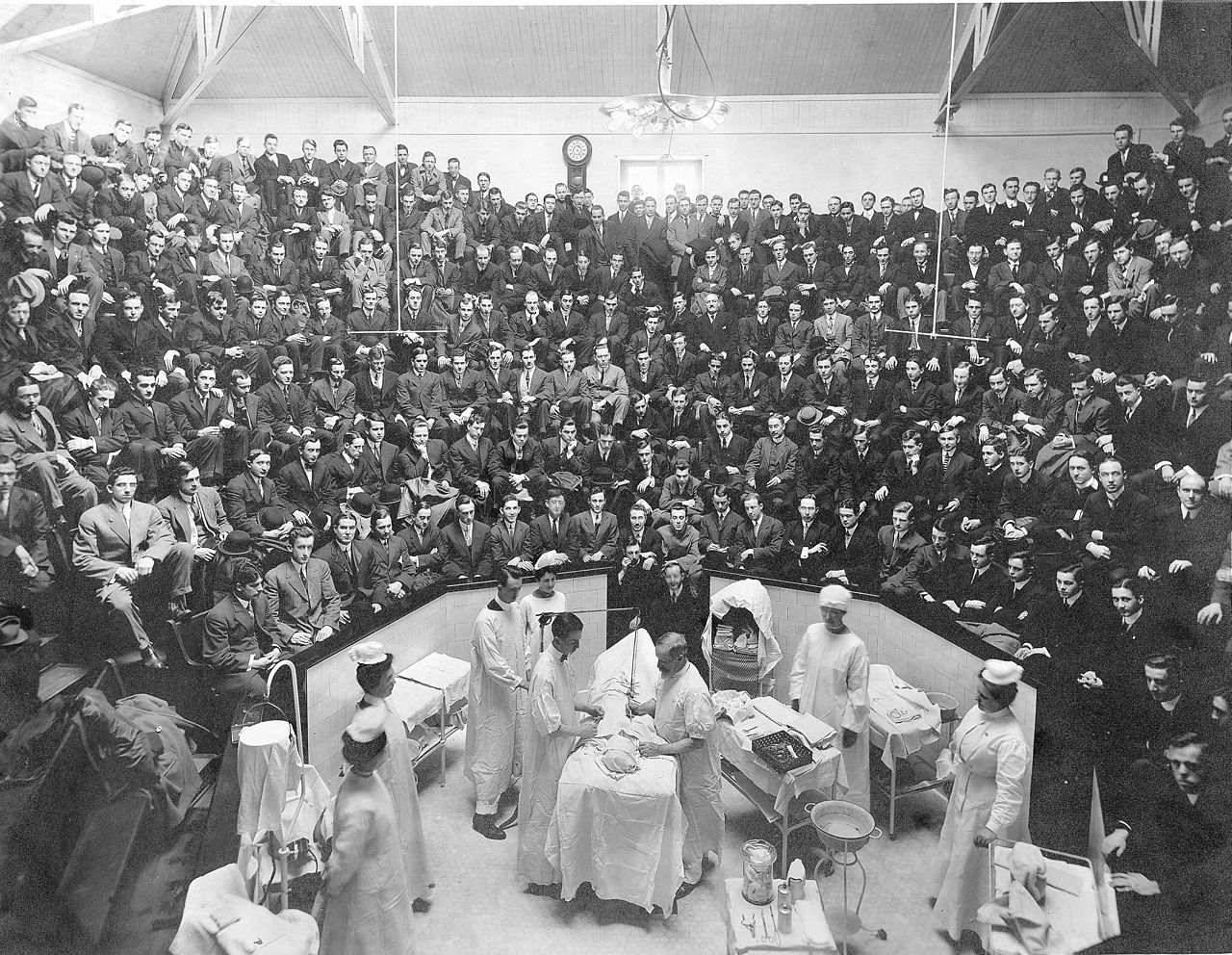

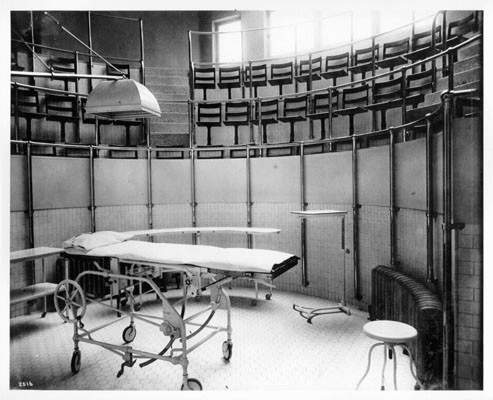

The most iconic symbol of medicine as a spectacle was the surgical amphitheater at Pennsylvania Hospital, built in 1804. This structure, famously known as the “Round Room,” was designed to provide a bird’s-eye view for spectators perched on steep tiers of wooden benches. At the center of this arena sat the operating table, positioned directly beneath a soaring glass dome—the only source of high-intensity light in the pre-electric era. Spectators who purchased tickets to these events witnessed the human body being “unveiled” in what was essentially a live, high-stakes broadcast.

The atmosphere in these halls was sensory overload: the smell of sawdust, strewn to soak up blood, mingled with the aroma of tobacco smoke used by the audience to mask the scent of decay. Despite the apparent gore, these “performances” were critical for education, demonstrating real organ topography. A surgeon in a black frock coat—long before the days of antiseptics—would narrate every movement, turning the procedure into an intellectual drama. This was the birth of the Philadelphia clinical school, where visual experience was held in higher regard than textbook theory.

Surgery as Ritual: The Era of Dr. Gross

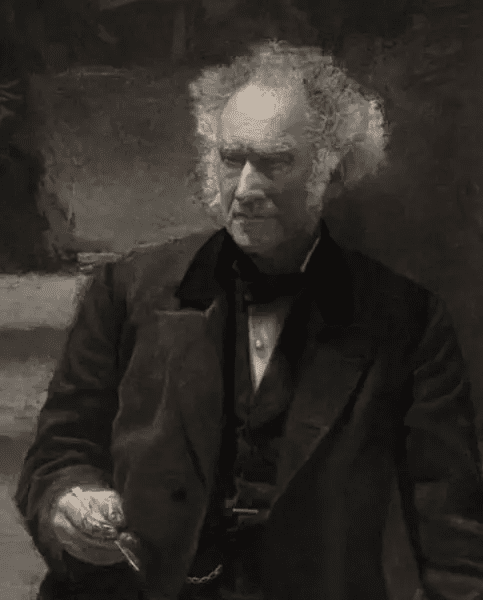

By the mid-19th century, Philadelphia medicine found its premier “director” in Dr. Samuel Gross. His lectures at Jefferson Medical College were legendary, and his persona was immortalized in Thomas Eakins’ monumental masterpiece, “The Gross Clinic.” This painting perfectly captures the zeitgeist: a majestic professor with a blood-stained scalpel explaining surgical details, surrounded by assistants and a crowd of observers in the shadows of the theater. Gross believed that a surgeon was not a mere craftsman but a “philosopher of action” whose work should be open to scrutiny and study.

Operations in this era were performed without effective anesthesia, as even ether had not yet entered common use. Consequently, speed was the ultimate measure of professional skill. Audiences held their breath as masters amputated limbs in mere minutes. It was a high-tension show where the stakes were higher than any theatrical opening night—it was a matter of life and death. The public nature of these procedures served as a form of quality control; a mistake was instantly visible, pushing doctors toward absolute anatomical precision.

The Mütter Museum: A Cabinet of Pathological Curiosities

As science moved beyond the operating room, it found a home in private collections, the most famous of which became the Mütter Museum. Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, a brilliant surgeon, amassed thousands of anatomical specimens, skeletons, and medical anomalies to illustrate the vast variability of the human form. In 1858, he donated his collection to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, creating a space where the “spectacle of science” continues today.

Key highlights of this permanent exhibition include:

- The Soap Lady. A woman’s body that, because of unique burial conditions, turned into adipocere (grave wax).

- The Giant’s Skeleton. A massive example of acromegaly that towers over standard specimens.

- The Hyrtl Skull Collection. Hundreds of European skulls were used to debunk the racial theories of phrenology common at the time.

- Harry Eastlack. The skeleton of a man whose muscles slowly turned into bone during his lifetime due to a rare genetic condition.

Every object in this museum is a frozen moment of disease or biological uniqueness, turning medical education into a visual journey that explores the very edges of what it means to be human.

Suppliers of “research material”: the dark side of the medical scene

The thriving anatomical theaters required a constant supply of teaching material—human bodies. Because the laws of the time did not provide enough legal cadavers, a grim black market emerged. “Resurrectionists,” or body snatchers, became an integral, albeit hidden, part of Philadelphia’s medical machinery. They raided fresh graves in “potter’s fields” to satisfy the hunger of anatomy professors who often turned a blind eye to the origins of their “teaching aids.”

While this aspect of science was rarely a public spectacle, it caused the greatest social upheavals. The most notorious scandal broke in 1882 when mass grave robbing was discovered at Lebanon Cemetery, with bodies traced back to Jefferson Medical College. The ensuing public outrage forced the Pennsylvania legislature to pass the “Anatomy Act,” which regulated the legal use of unclaimed bodies for research. This brought the curtain down on the era of grave robbing, forcing medicine to move toward a more civilized and respectful partnership with the public.