Cholera struck Philadelphia repeatedly throughout the 19th century. This devastating disease claimed many lives, yet at the same time, it spurred the development of public health and hygiene systems. Back then, doctors still debated its causes, leading to various treatment and prevention methods. Eventually, though, they uncovered the truth, putting a definitive end to cholera outbreaks in the city. Learn more about the history of cholera epidemics and their conquest in this article on iphiladelphia.

Cholera Outbreaks in Philadelphia

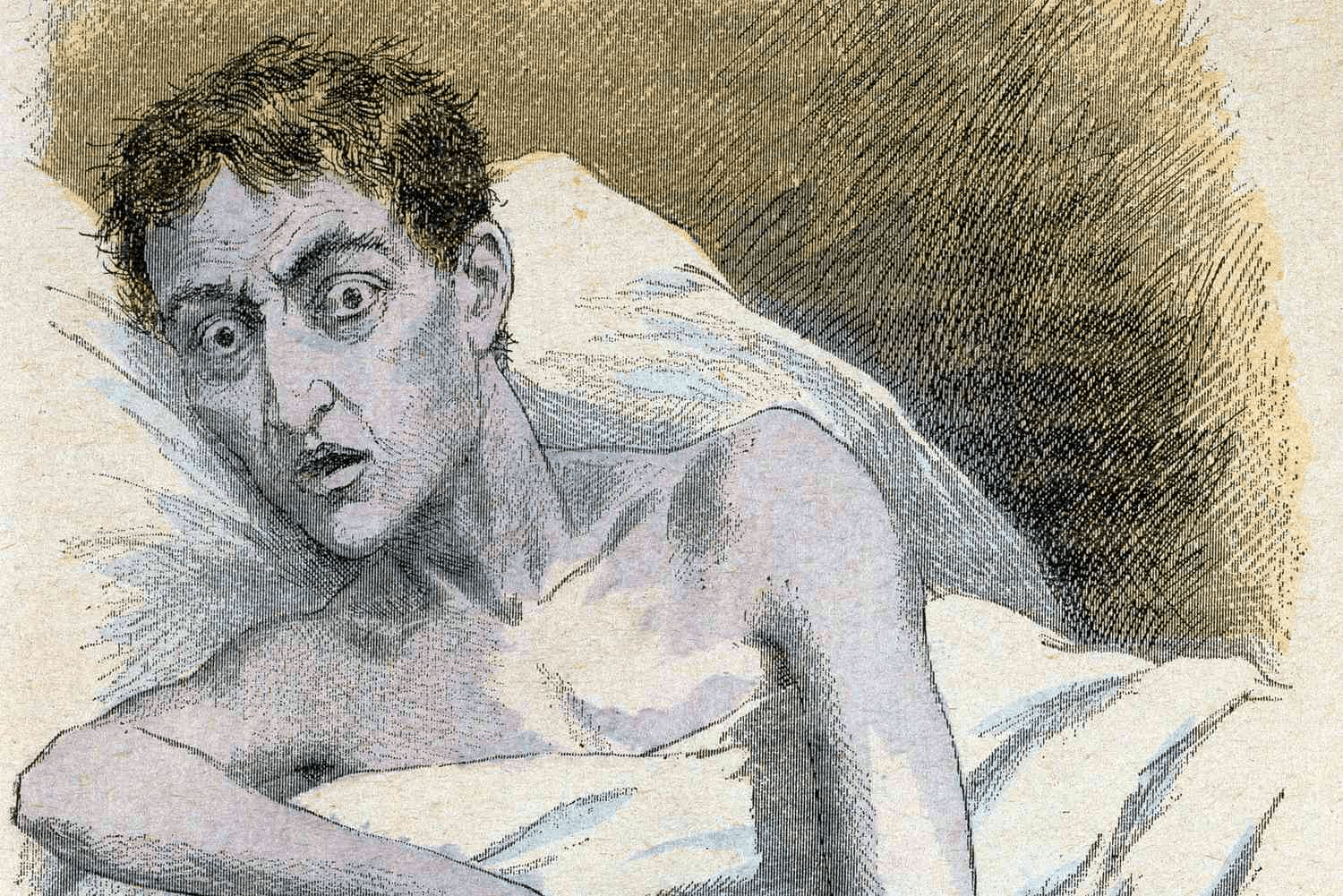

Before the 19th century, cholera was endemic to faraway India. The disease brought severe pain and dehydration due to intense diarrhea and vomiting. In many cases, these symptoms proved fatal. In 1817, it spread beyond India and even its continent, thanks to advancements in seafaring.

In Western Europe, cholera was recorded in 1831, and by the following year, it had appeared in North America. Philadelphia, for instance, experienced cholera outbreaks in 1832, 1849, and 1866. These epidemics spurred significant changes in hygiene and healthcare standards.

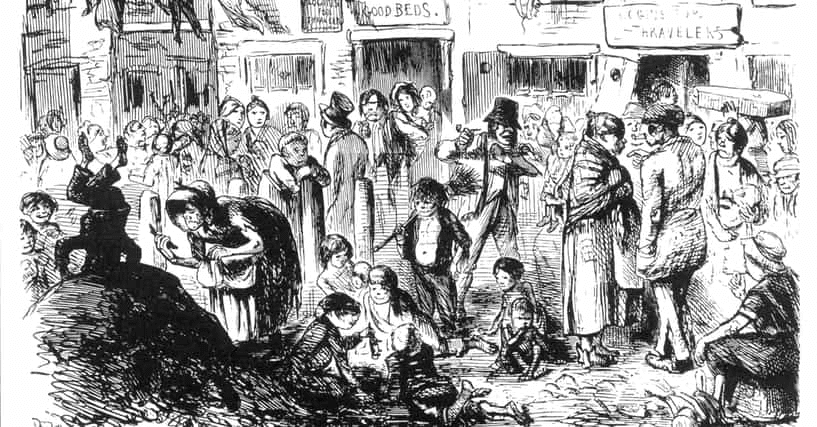

During the first outbreak, specialists from the local College of Physicians claimed the disease wasn’t new. They believed that what happened was a spread of local diarrhea, caused by harmful vapors from accumulated city filth. Doctors vehemently denied the possibility of an infectious agent. Instead, they asserted that the disease primarily affected the poor and “immoral,” as well as certain ethnic groups.

The only positive outcome was the doctors’ recommendation to the Board of Health to clean up Philadelphia’s unsanitary conditions. They also advocated for expanding the hospital network and promoting hygienic practices among the populace. These recommendations were implemented almost immediately. Meanwhile, churches and private charities provided nurses and treatment spaces for the sick. The epidemic ended in mid-September, with 935 deaths recorded.

The highest number of deaths was recorded in the state prison. Hygienic conditions there were appalling, as was the general state of the incarcerated prisoners. However, doctors believed this supported their theory about the disease spreading among “immoral” citizens. It’s worth noting that authorities released prisoners whose crimes weren’t severe, and these individuals then inadvertently spread cholera.

Characteristics of the Cholera Epidemic in Philadelphia

Cholera struck the city again in 1849. Philadelphia’s population had doubled by then, and 747 people died. During this epidemic, officials once again fought against filth and built new hospitals. They thought these methods were working, as the mortality rate was decreasing. However, from 1850 to 1854, cholera returned repeatedly.

The death rate from this disease in Philadelphia was indeed surprisingly low, lower than in other American cities:

- The truth was that the city used drinking water from the Fairmount Reservoir.

- This same water was used to clean Philadelphia’s streets, but the cholera vibrio spread precisely through contaminated drinking water.

- Therefore, it was a clean water source, not the absence of dirt, that was the reason for the city’s lower mortality rate.

In areas south of downtown, where African Americans and Irish immigrants lived, the mortality rate was four times higher. Doctors still attributed this to poverty and the “racial” nature of the disease. In reality, these communities simply lacked access to clean drinking water, which facilitated the spread of cholera and led to high mortality.

Searching for the True Cause of the Epidemic

The College of Physicians continued to defend their theory about the disease’s nature and causes. However, other doctors began to voice ideas that were revolutionary at the time.

West of Philadelphia, in Lancaster County, cholera erupted in the fall of 1854, claiming 127 lives. Before this, the epidemic had been in a city from which residents fled by rail to other regions of the country. Dr. Jackson from Philadelphia visited the sick and concluded the infectious nature of cholera and its human-to-human transmission. He asserted that the disease affected everyone, regardless of skin color or social status.

Dr. Atlee from Lancaster supported his colleague. He agreed with this view and also identified microscopic particles in the victims’ excrement. This, in essence, laid the groundwork for the germ theory, which soon became an undeniable truth. The analyses of American doctors replicated the results of British physician John Snow. Unfortunately, their research didn’t gain widespread attention, but remained significant in the history of medicine.

Cholera again spread in Philadelphia in 1866, 1891, and 1899. Initially, doctors still clung to their previous views, but they eventually agreed that the disease spread through contact with infected biological fluids. Therefore, disinfectants began to be used in the fight against epidemics, which was a crucial and life-saving step for the city’s residents.

The return of cholera in the 1890s prompted the Board of Health’s decision to install a drinking water filtration system. The 20th century saw significant expansion of Philadelphia and an increase in population, after which the sewage and water purification systems were modernized. Subsequently, no more cholera outbreaks were recorded in the city.