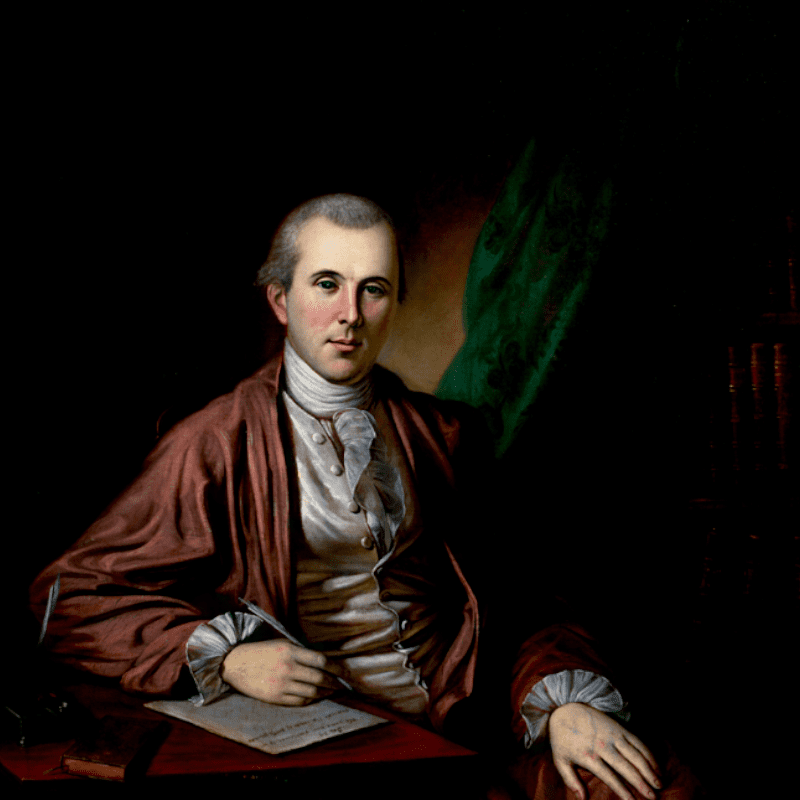

Every American knows the key figures among the Founding Fathers who spurred America’s growth. Benjamin Rush was one of them, but his contributions extended far beyond politics. He championed the Enlightenment movement, supported the American Revolution, advocated for improved women’s education, and much more. Rush became an integral part of the history of modern America and medicine. Read more at iphiladelphia.

Benjamin Rush’s Early Years

The future Founding Father was born on a cold winter day, January 4, 1746, in Byberry. His parents, John and Susanna Rush, were Americans of English descent. Benjamin’s early years were spent immersed in nature, as his family lived on a plantation. Like many families of that era, they had numerous children, and Rush himself was the fourth of seven offspring.

Benjamin first experienced the sting of death in 1751, when his father passed away at the age of 39. The entire burden of raising the children and earning a living fell upon Susanna’s fragile shoulders. Life lost its vibrancy for the widowed mother, as survival demanded constant work, leaving very little time for her own children.

Due to the family’s struggles, Benjamin was sent to live with his aunt at the age of eight to pursue his education. His brother, Jacob, also moved to the unfamiliar place, and together they began attending school.

A Young Man’s Education

In 1760, at just 14 years old, Rush completed his education at the College of New Jersey, where he earned a bachelor’s degree. From 1761 to 1766, Benjamin studied under John Redman, who later insisted that the young man continue his education. He went on to attend the University of Edinburgh, where he earned his master’s degree.

Thanks to his diligent studies, Benjamin managed to learn French, Italian, and Spanish.

Career Development and Engagements

After completing his extensive education, Rush finally returned home. In Philadelphia, he decided to establish his own medical practice. However, alongside starting his new venture, he also taught at a college, later becoming a professor.

Benjamin was the first person to write and publish a chemistry textbook in the U.S. Given his successful start in this field, he went on to release several volumes on medicine and patriotic essays.

His career was undoubtedly important to him, but he also began to consider his personal life. On that front, things weren’t as cheerful. Before the start of the Revolutionary War, he became engaged to a beautiful young woman named Sarah Eve. Tragically, his fiancée did not live to see their wedding day.

After this difficult and painful experience, Rush eventually mustered the courage to propose a second time. His chosen bride was Julia Stockton, whose father would later become one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. The wedding took place on January 11, 1776.

Political, Public, and Medical Endeavors

Rush’s activities and stance were quite clear. He first became a member of the “Sons of Liberty” organization, and later, due to his views, he was chosen to participate in the provincial conference. The purpose of this conference was to select delegates who would go to the Continental Congress.

Once again, thanks to his stance and opinions, Benjamin was trusted and consulted. One such person was Thomas Paine, who wanted to hear Rush’s thoughts on the struggle against British rule. Paine’s work was published under the title “Common Sense,” and Benjamin wholeheartedly supported him throughout the writing process.

At the Continental Congress, Rush represented Pennsylvania, and on its behalf, he became a signer of the Declaration of Independence. But his contribution to improving the situation didn’t end there. He accompanied Philadelphia police officials when the British army captured the city and much of New Jersey.

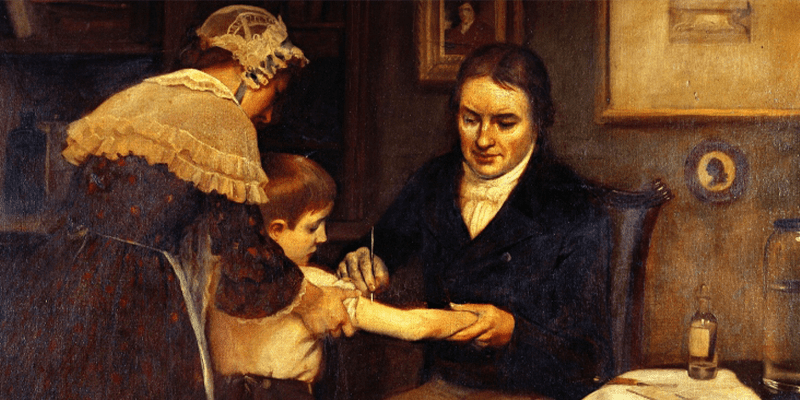

Every war brings a large number of wounded, leading to a shortage of medical personnel and resources. The struggle for independence was no exception, though most deaths were from typhoid fever, yellow fever, and other diseases. Medicines to combat these illnesses were scarce. Therefore, Rush drafted an order that mandated directing all efforts toward preserving the army’s health.

Benjamin’s rather fierce struggle with members of the medical committee over the lack of funding for aid led to his full resignation in 1778. However, his medical career did not suffer from this. After the long-awaited victory in 1783, Rush was appointed to work at Pennsylvania Hospital. He continued to help his patients there until his death.

Rush’s Views on Slavery, Capital Punishment, and Women’s Status

Benjamin Rush was a prominent abolitionist. This conviction formed during his travels to Edinburgh, where he witnessed numerous slave ships. In 1773, he decided to write a pamphlet addressing the public. In these writings, he thoroughly condemned the slave trade, hoping every word would be heard.

Rush drew people’s attention to the fact that African Americans were intelligent individuals, in no way inferior to people of other races. However, despite his condemnation of those who supported slavery, he himself bought an enslaved worker in 1776.

Rush also became an opponent of capital punishment. As an alternative to this barbaric form of punishment, he proposed life imprisonment. In his opinion, prisoners should work, live in solitude, and receive religious enlightenment. Thanks to Rush’s ideas, Pennsylvania decided to abolish the death penalty for all crimes except first-degree murder.

Thanks to Benjamin, an academy for young women was established in Philadelphia. He proposed that all girls from the upper echelons of society should have the opportunity to receive an education. The curriculum included English, vocal music, instrumental music, dancing, science, bookkeeping, history, and philosophy. However, he opposed co-education and insisted that all young people should know the commandments of the Christian religion.

Expanding Medical Views and Final Years

Benjamin Rush was a strong advocate for bloodletting. Later, of course, it became known that such a practice was very harmful to humans. However, he believed that this type of treatment could cleanse the body.

During his medical discoveries, he wrote that the yellow fever epidemic could be cured by bloodletting. Sometimes, he managed to help his patients this way, though only a small number.

Rush tried to find cures for diseases. Some procedures he later admitted were failures. On one occasion, he was accused of involvement in a death from yellow fever. For this “libel,” Rush filed a lawsuit, which he successfully won and received compensation.

But Benjamin continued to follow flawed paths in addressing medical treatments, which led to a reduction in his medical practice. Later, he was suspected of direct involvement in the deaths of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, but no one was ever able to prove it.

Despite his questionable medical decisions, Rush made a rather significant contribution by establishing a state dispensary for low-income individuals in Philadelphia. He also attempted to classify various mental illnesses, identify their causes, and suggest further treatment. But even there, Rush deviated from reality, believing that most such diagnoses were caused by changes in a person’s blood circulation or overwork.

Despite all his efforts in medicine, Rush could not save himself. He died from epidemic typhus. Death claimed Benjamin on April 19, 1813. And despite his flawed medical decisions, he was one of those whose mistakes the next generations learned from. But his greatest achievement was the development and establishment of our independent country.