The development of the world’s first automatic electronic digital computer, ENIAC, marked the dawn of the information age. Created in Philadelphia during World War II, this device made history as the first general-purpose, non-mechanical computer.

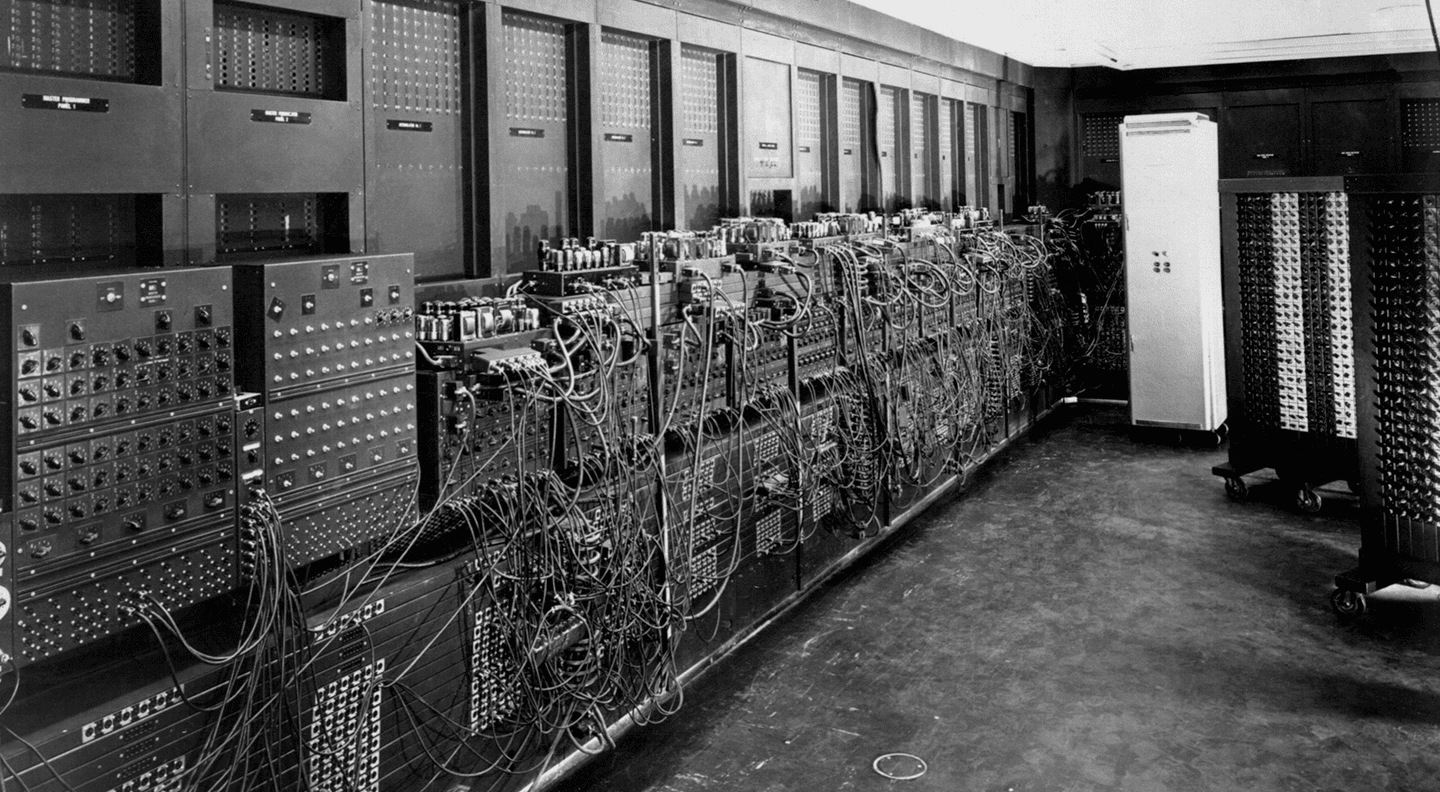

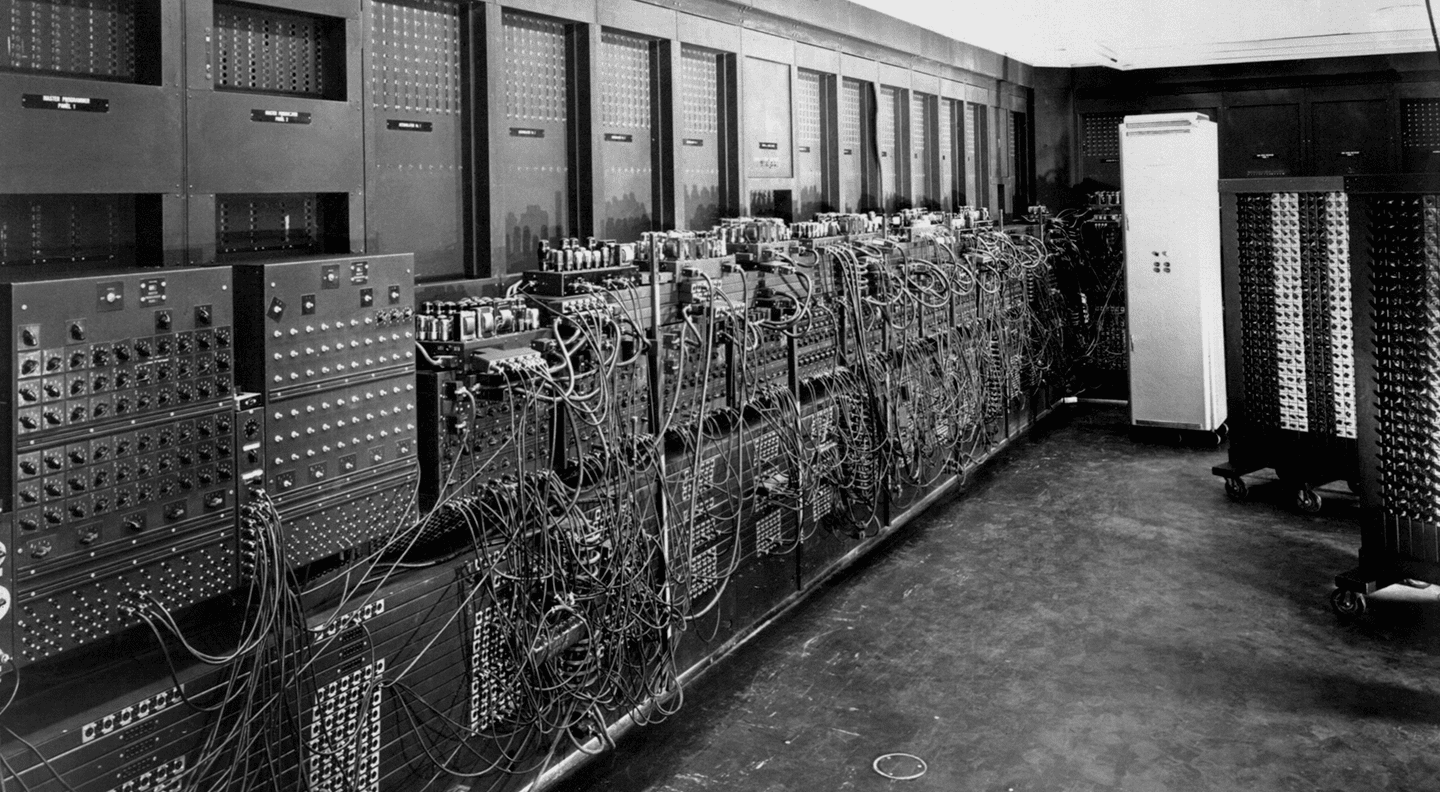

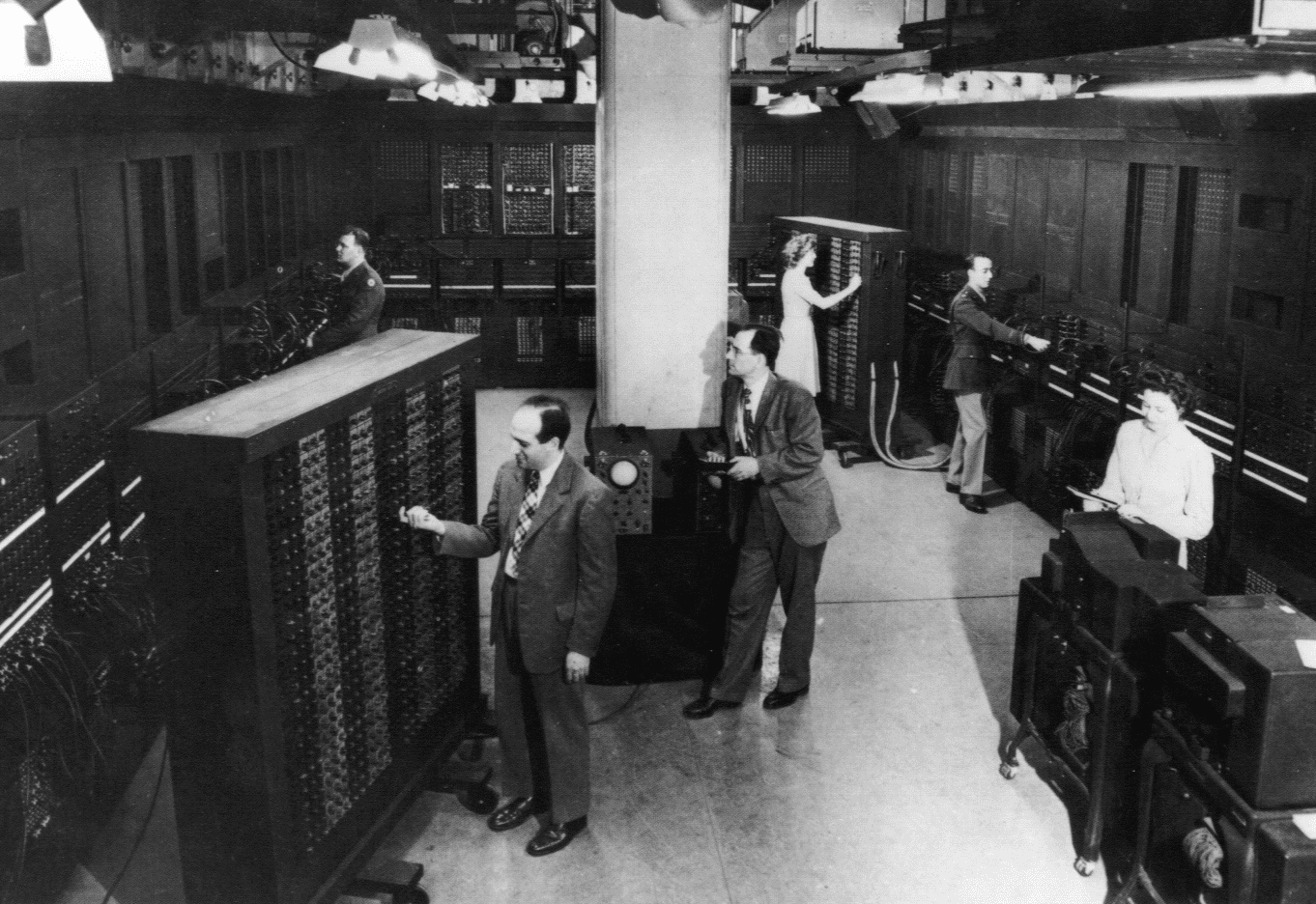

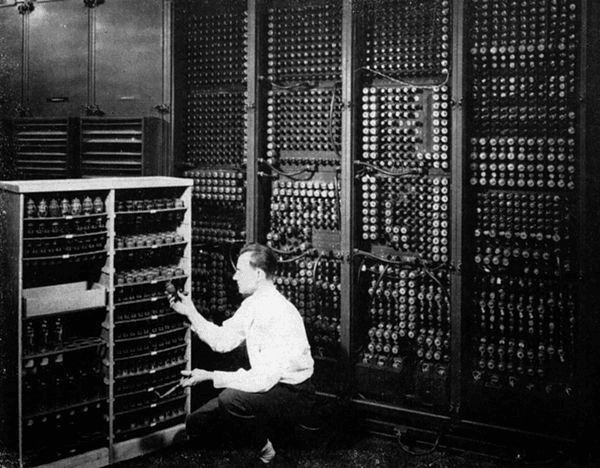

It was unveiled to the public in 1946 at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering. The machine was a massive sight, consisting of 40 cabinets, each 9 feet tall, and packed with 18,000 vacuum tubes, 6,000 switches, 10,000 capacitors, and 1,500 relays. ENIAC was capable of performing a wide range of calculations. Notably, women played a crucial role in its development. You can discover more about the history of the first computer at iphiladelphia.

What Was ENIAC?

The world’s first programmable computer was named ENIAC, an acronym for “Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer.” Developed throughout the 1940s in Philadelphia, the research took place at the University of Pennsylvania’s electronics institute. The new machine took up 1,800 square feet (167 sq. m), weighed about 30 tons, and consumed up to 150 kW of power. The total development cost came to half a million dollars.

The primary goal for creating this machine was to solve a pressing issue of the time: automating the calculation of ballistic tables for the military. The computer’s architecture was designed by John Mauchly, J. Presper Eckert, and John von Neumann, all of whom were working at the University of Pennsylvania.

The scientists decided against using mechanical relays, opting instead for vacuum tubes as the core of their design. The machine contained nearly 18,000 of them, along with thousands of relays, silicon diodes, resistors, and capacitors. Its processing power was impressive for the time, capable of performing 300 multiplications or 5,000 additions per second.

The History of the First Computer

The military’s need for fast and accurate calculations dated back to World War I. At that time, the U.S. began using mathematical calculations to determine artillery firing trajectories. This work had to be done by hand and was primarily handled by women, since most men were either at the front or engaged in other war-related jobs.

The demand for firing tables and other ballistic data led to the establishment of the Ballistic Research Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. This demand only grew, intensifying sharply after the U.S. entered World War II. It became clear to the Laboratory that their calculations had to be automated, justifying a significant investment in developing a specialized machine.

To achieve this, a contract was awarded to the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering. Their specialists were tasked with rapidly developing a powerful electronic computing machine capable of various calculations. The U.S. government had previously involved the school’s faculty and even students in secret military research projects. Furthermore, the school had established a training course on operating complex weapons systems and funded a military training program in engineering, science, and management. Consequently, there was little doubt the scientists could handle the task.

Professors John Mauchly and John von Neumann, along with graduate student J. Presper Eckert, began work on the project on June 5, 1943. They focused on designing the new computer’s architecture, completing it in 1945. The device was presented to the public on February 15, 1946. The project was initially budgeted at $150,000, but the final cost rose to $400,000.

At the time, scientists around the world were developing large computing machines and calculators, but they could only perform single types of calculations. This is what made ENIAC unique: it was reprogrammable and could solve various types of problems. It also operated at incredible speeds, performing thousands of precise calculations per second.

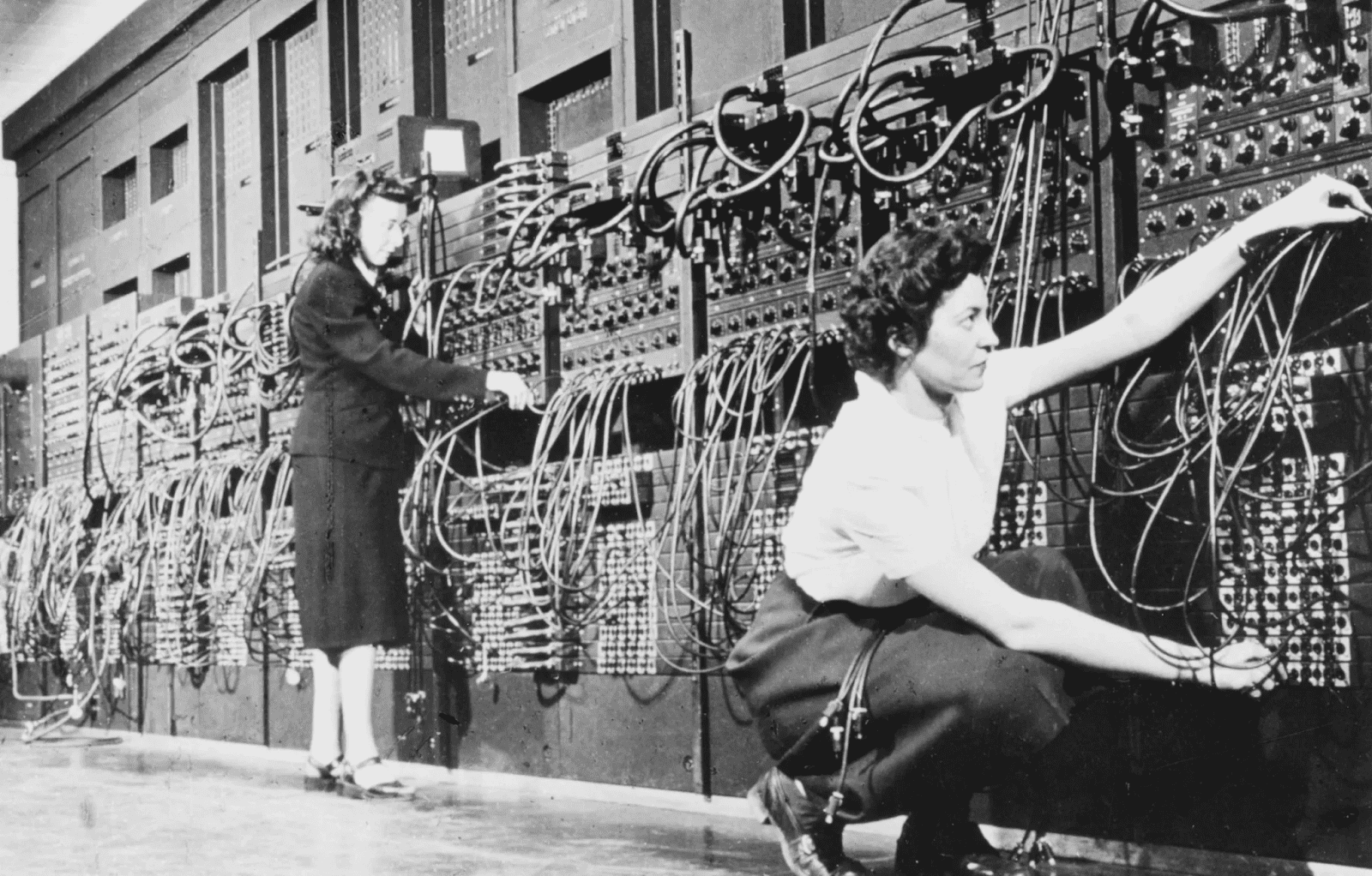

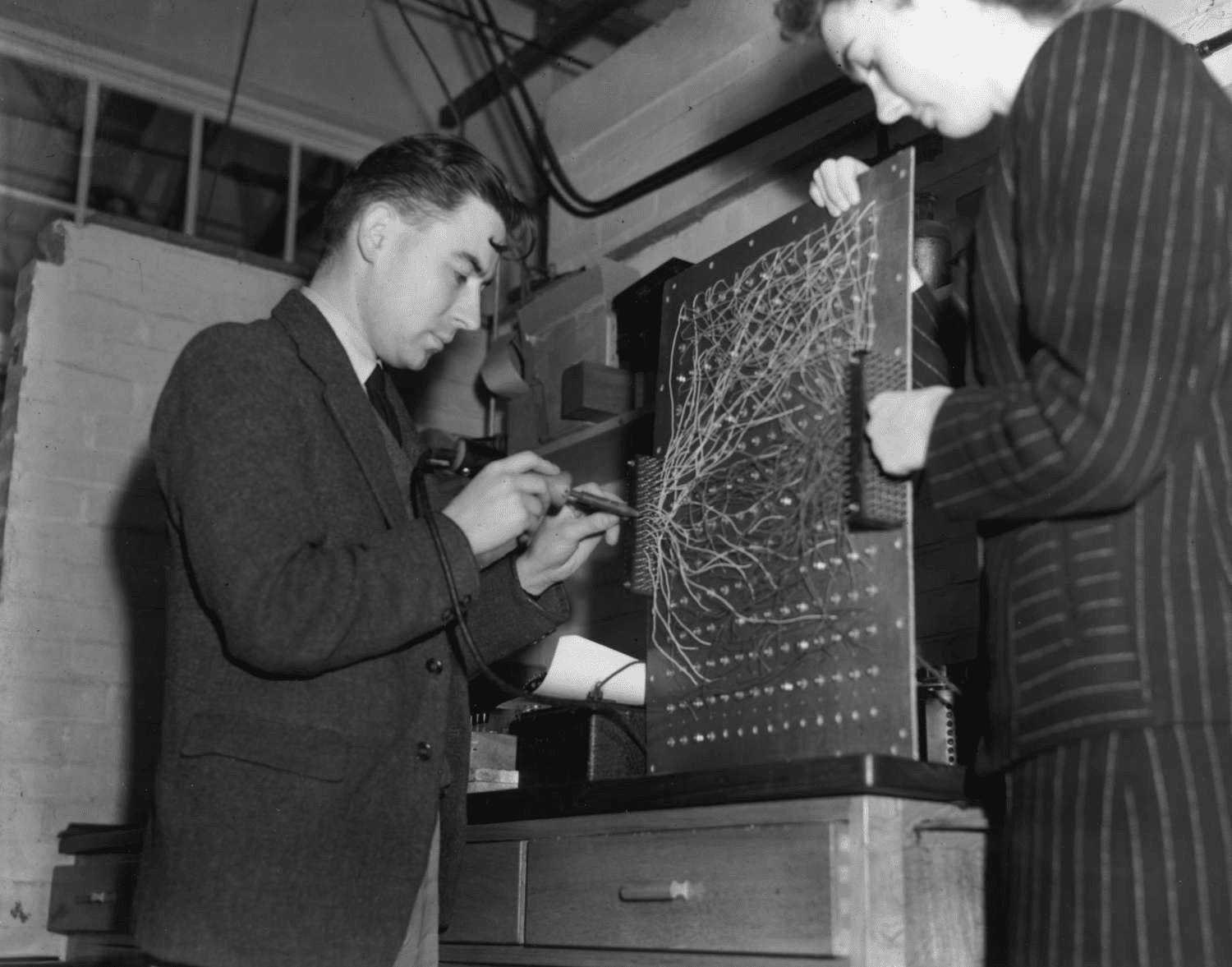

It’s important to note that six female mathematicians were also crucial to ENIAC’s development: Marlyn Meltzer, Betty Jennings, Kay McNulty, Frances Bilas, Betty Snyder, and Ruth Lichterman. They taught themselves how to program the computer using only logic diagrams and blueprints, and they even wrote its operating manual. Initially, their role was overlooked and didn’t receive public recognition. In fact, in photographs with the machine, they were often labeled simply as “models.” It wasn’t until decades later that the full story of their indispensable work—without which the computer’s launch would have been impossible—came to light. In 1997, all six women were inducted into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame, and a film was made about their contributions.

ENIAC in Use

After becoming operational, ENIAC was primarily used for ballistic calculations, as well as for tasks related to nuclear weapon production, wind tunnel design, cosmic ray research, and weather forecasting. In mathematics, it helped with studying and analyzing random rounding errors.

As per the agreement, the machine was moved from the University of Pennsylvania in 1947 and installed at the Ballistic Research Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground. There, it continued to be used for weather modeling and calculations for the hydrogen bomb.

The Project’s and Developers’ Future

The computer was decommissioned on October 2, 1955. Shortly after, it was dismantled, and its various parts were sent to museums across the U.S. and the U.K. for preservation. Components can be seen today at the Computer History Museum, the National Museum of American History, the Science Museum in London, the Smithsonian Institution, and other institutions.

In 1973, a U.S. federal court invalidated the patent for ENIAC. From that point on, the world’s first electronic digital computer officially became public domain. The anniversary of its creation is celebrated every year on February 15.

As for its developers, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert left the University of Pennsylvania after the project concluded. In late 1947, they founded their own company, the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, headquartered in Philadelphia. Together, they continued to develop new computer technologies, including:

- the second version of the Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer (EDVAC II),

- the Binary Automatic Computer (BINAC),

- the Universal Automatic Computer (UNIVAC).

In 1950, the company was acquired by the Philadelphia-based machine manufacturer Remington Rand. As part of this larger corporation, Mauchly and Eckert’s work was not as productive as before, and other companies began to pull ahead.

However, thanks to the development of ENIAC and the contributions of its six female programmers, Philadelphia has cemented its place in history as the birthplace of the modern computer. The successful completion of this project laid the groundwork for hundreds and thousands of scientists who continued to innovate and advance computing technology across the country and around the world.