The Philadelphia chromosome (Ph chromosome) is far more than a microscopic anomaly; it is a fundamental discovery that, for the first time in medical history, proved the genetic nature of cancer. Discovered in 1960 in the heart of Pennsylvania’s largest city, it became the “key” that unlocked the era of targeted therapy. This breakthrough transformed a once-fatal blood cancer into a manageable condition, demonstrating how a single point of failure in the hereditary chain can wreak havoc on the entire body. The history of its study is a forty-year scientific detective story, where every step brought humanity closer to understanding the mechanisms of cellular life and death.Details of this groundbreaking discovery: who made it, how it happened, the implications for all leukemia patients, and the cure for the disease at iphiladelphia.net.

An Accidental Triumph at Fox Chase

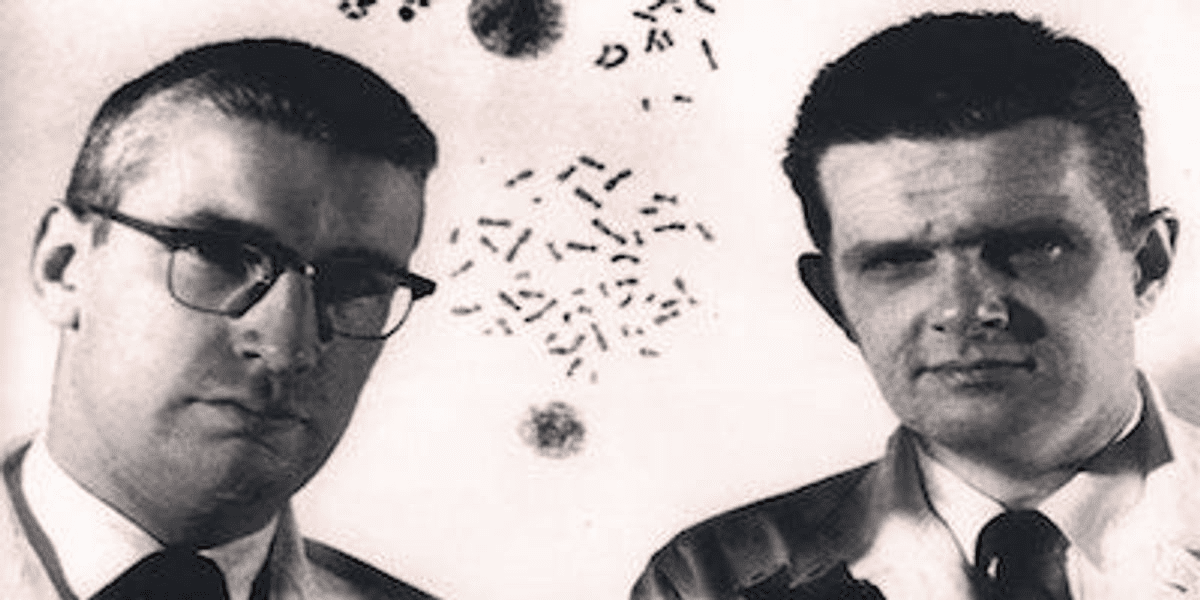

It all began within the walls of the Fox Chase Cancer Center, where two young specialists—Peter Nowell from the University of Pennsylvania and David Hungerford—were conducting routine observations of cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). In those days, genetics was merely a supporting discipline, and scientists lacked advanced staining techniques for their samples. However, the researchers’ keen eyes caught a strange detail: the white blood cells consistently appeared to be missing a portion of their genetic material.

They observed that the 22nd pair of chromosomes in these patients was significantly shorter than in healthy individuals. This was the first documented evidence linking a specific oncological pathology to a distinct chromosomal defect. At the time, this was a radical proposition; the prevailing scientific dogma held that cancer was caused exclusively by viruses or environmental toxins. Nowell and Hungerford’s discovery shattered these old beliefs, laying the cornerstone for molecular biology in oncological practice.

Anatomy of a Defect: The Birth of a Name

Since the discovery took place in the heart of Pennsylvania, the abnormal structure was officially christened the Philadelphia Chromosome. This designation became a source of civic pride, establishing the city as a global leader in hematological research. Throughout the following decade, scientists worldwide scrambled to understand exactly where the missing genetic fragment went and what role its absence played in the development of malignancy.

During the 1960s, studying the genetic code was akin to trying to read a book through frosted glass. Cytogenetic technology at the time only allowed for blurry outlines of chromosomes, meaning scientists could only confirm the “shortening” of chromosome 22. Many skeptics dismissed it as a simple deletion—a random loss of genetic code resulting from the disease itself.

However, the Philadelphia-based researchers showed remarkable persistence. They proved that this defect was not a byproduct of the body’s deterioration but a stable marker found in nearly every patient with CML. This was the first time in medical history that a specific type of cancer was proven to be caused by a specific “break” in the genes.

Recognizing the stability of the Ph chromosome opened the door to a new era in medicine.

- Diagnostic Precision. For the first time, doctors could confirm cancer at the molecular level rather than relying solely on symptoms.

- Personalized Approach. The Philadelphia chromosome served as the first “genetic passport” for a tumor. This allowed treatment to be tailored to a patient’s individual profile, eventually leading to targeted therapies.

- The Harbinger of Revolution. The study of the Ph chromosome would, decades later, lead to the creation of the legendary drug Gleevec (Imatinib), which turned a fatal blood cancer into a manageable chronic condition.

Thanks to the tenacity of Philadelphia’s scientific community, what initially seemed like a mere “microscopic defect” became the foundation of modern oncogenetics. The city didn’t just name the chromosome—it gave the world hope.

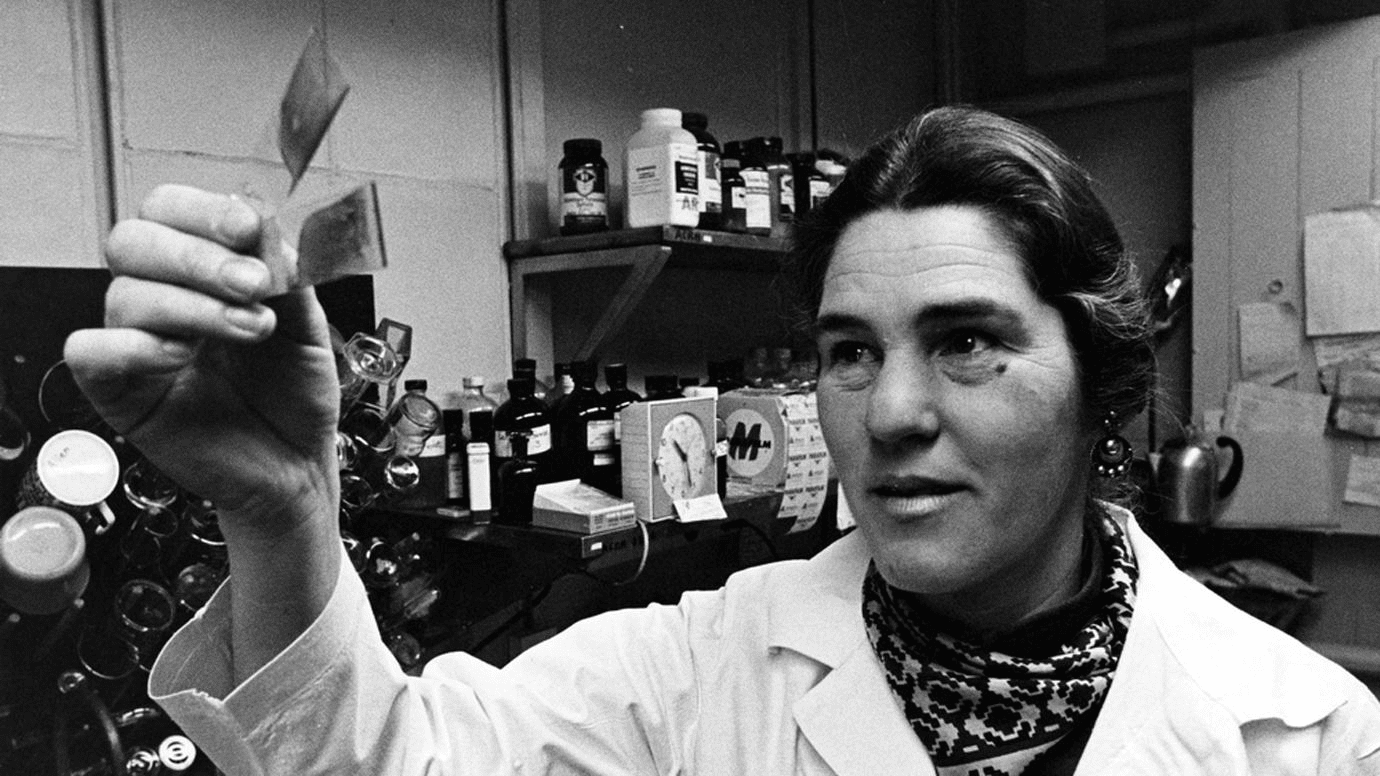

Janet Rowley and the Great Rearrangement

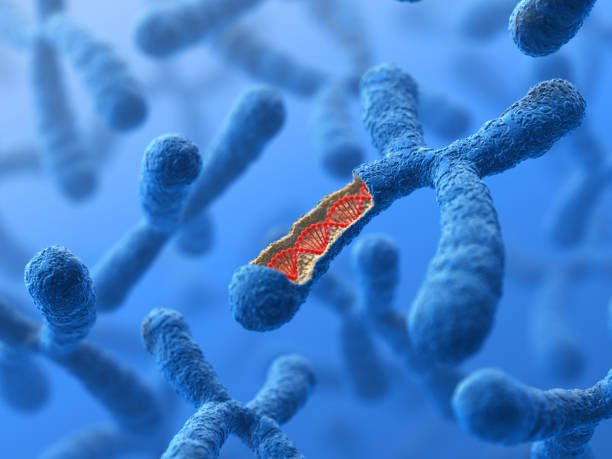

The true revolution in understanding this phenomenon occurred in 1973, thanks to the work of geneticist Janet Rowley in Chicago. Utilizing groundbreaking fluorescent labeling techniques, she reached a stunning conclusion: the genetic material wasn’t simply missing. Instead, a translocation occurred—a reciprocal swap of segments between chromosomes 9 and 22.

- The Exchange Mechanism: A fragment of chromosome 9 moves to chromosome 22, attaching itself to the BCR gene.

- The Result: The creation of a hybrid “Frankenstein gene” known as BCR-ABL, which does not exist in nature under normal circumstances.

This genetic “dance” causes the cell to incessantly produce a specific enzyme called tyrosine kinase. This protein acts like a faulty light switch stuck in the “on” position, forcing white blood cells to divide at an uncontrollable rate. Rowley’s discovery explained the biological engine driving leukemia, providing scientists with a clear target for future medications.

Blocking the Signal: The Gleevec Revolution

Once the enemy had a face, scientists began searching for a way to “turn off” the abnormal protein. In the late 1990s, the efforts of Brian Druker and other researchers led to the development of imatinib (marketed as Gleevec). This was the world’s first “smart drug,” which—unlike traditional chemotherapy—did not kill cells indiscriminately. Instead, it specifically blocked only the defective enzyme created by the Philadelphia chromosome.

The results were nothing short of miraculous. Patients whose life expectancy was previously measured in months were suddenly able to live for decades by simply taking one pill a day. This discovery transformed a fatal hematological disease into a chronic condition, similar to diabetes. Gleevec proved that a deep understanding of a genetic error could lead to the creation of the perfect weapon against cancer.

A New Paradigm in Cancer Care

Today, the story of the Ph chromosome is taught in medical schools worldwide as a masterclass in the scientific method. It proved that cancer is not a monolithic monster but a collection of specific molecular errors, each of which can potentially be corrected. The legacy of the Philadelphia scientists shaped the concept of precision medicine, where therapy is tailored to an individual’s specific mutation.

The success in treating CML inspired the creation of hundreds of other targeted drugs for lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma. Researchers are now searching for the “Philadelphia chromosome” equivalent for every type of malignancy. The city where two scientists once looked closely through a microscope will forever remain the epicenter of a great intellectual victory that continues to offer hope to millions.

Key Milestones in Ph Chromosome Research

| Year / Event | Key Figures | Scientific and Clinical Outcome |

| 1960: Discovery | P. Nowell, D. Hungerford | Discovery of the first genetic abnormality linked to cancer. |

| 1973: Translocation | Janet Rowley | Proof that the defect is a gene swap between chromosomes 9 and 22. |

| 1980s: The Hybrid | Research Group | Identification of the BCR-ABL fusion gene that triggers the disease. |

| 1990s: Gleevec | Brian Druker et al. | Creation of the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (targeted therapy). |

| Today | Global Community | Transition to personalized oncology based on DNA profiling. |

Sources:

- https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/philadelphia-chromosome;

- https://geneticeducation.co.in/philadelphia-chromosome-bcr-abl1-fusion-gene-and-its-role-in-cancer/;

- https://www.emedicinehealth.com/is_philadelphia_chromosome_curable/article_em.htm;

- https://easybiologyclass.com/philadelphia-chromosome-and-oncogenic-bcr-abl-gene-translocation-in-cml/.