When we hear the name Philadelphia Museum of Art, our first thought is almost always the legendary steps, immortalized by the Rocky Balboa film series. But once you step away from the famous bronze statue, you enter a true epicenter of global culture. This monumental institution is far more than just a repository of artifacts. It’s a portal through millennia of art: from meditative Asian temples to the rebellious canvases of the Post-Impressionists. The facility is a towering testament to the ambitions of American culture and its dynamic history. Proudly rising above the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, this place not only safeguards priceless treasures but is also a living exhibit itself.

Why did this particular Philadelphia treasury become one of the most influential in the United States, and what unexpected masterpieces does it conceal behind its majestic columns? This is the story of how a single museum became a defining feature of an entire city’s cultural identity. We explore the details further on iphiladelphia.net.

World’s Fair Legacy and the Birth of an Idea

The museum’s founding dates back to 1876 and the Centennial Exhibition—the first major World’s Fair held in the United States—which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. An elegant Memorial Hall was specifically constructed to house the art exhibition. Its historically inspired architecture was intended to symbolize a new level of American cultural aspiration.

Just one year later, in 1877, the decision was made to transform the exhibition space into a permanent institution: the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art. This initial focus on “industrial art” was crucial. It demonstrated the young United States’ commitment not only to collecting masterpieces but also to educating a new generation of designers and artisans, merging aesthetic beauty with industrial development.

The Construction Timeline

As the original space in Memorial Hall rapidly became inadequate for the growing collections, the need for a new, grander structure emerged in the early 20th century.

- 1917: The final site for the future building was determined—on a hill in Fairmount Park, serving as the dramatic terminus for the new Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

- 1919: Philadelphia Mayor Thomas B. Smith laid the cornerstone of what was to become the city’s temple of art.

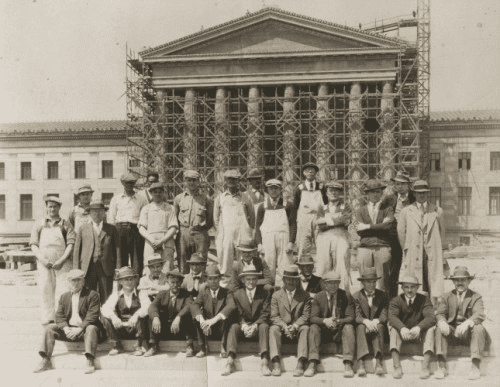

- The 1920s: Active construction began under the joint design of architects Paul Cret and Horace Trumbauer. The style chosen was Neo-Grec (or Neoclassicism), intended to convey the grandeur and timelessness of classical art.

- 1917: The official opening of the first section of the main building took place. Although many galleries remained empty, the opening marked the completion of a significant phase. The structure appeared as three interconnected pavilions, clad in the golden-beige Kasota limestone that became its signature material.

- The 1930s: Despite the Great Depression, interior outfitting and gallery filling continued. A large portion of the work was financed by WPA (Works Progress Administration) programs, which allowed dozens of exhibition spaces to be completed.

A unique figure in this process was the architect Julian Abele, the chief designer in Trumbauer’s firm and the first African American graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture school. He was responsible for the final blueprints, perspectives, and the overall artistic refinement of the structure, although his substantial contribution was long overlooked.

From Duchamp to the Orient

The collection, which numbers over 240,000 objects, is striking in its breadth and depth. American art is a crowning jewel, especially works connected to Philadelphia. A prime example is “Gross Clinic” by Thomas Eakins (1875), a stunningly realistic depiction of surgery that sparked scandal and was initially rejected from the Centennial Exhibition due to its overwhelming frankness.

The museum serves as the definitive home for Marcel Duchamp. It holds the most important collection of the Dadaist artist’s works outside of Europe, including his enigmatic masterpieces:

- “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2”;

- “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” widely known as “The Large Glass.” This complex, multi-year installation on two glass panels—made with oil, lead wire, and even dust—was famously declared “definitively unfinished” by the artist and holds a singular place in global art history.

Beyond Western art, the museum boasts an exceptionally strong Asian collection, featuring entire architectural ensembles, such as a Chinese ceremonial hall and a Japanese teahouse. This allows visitors to be literally transported to a different era and culture.

The Steps to Hollywood

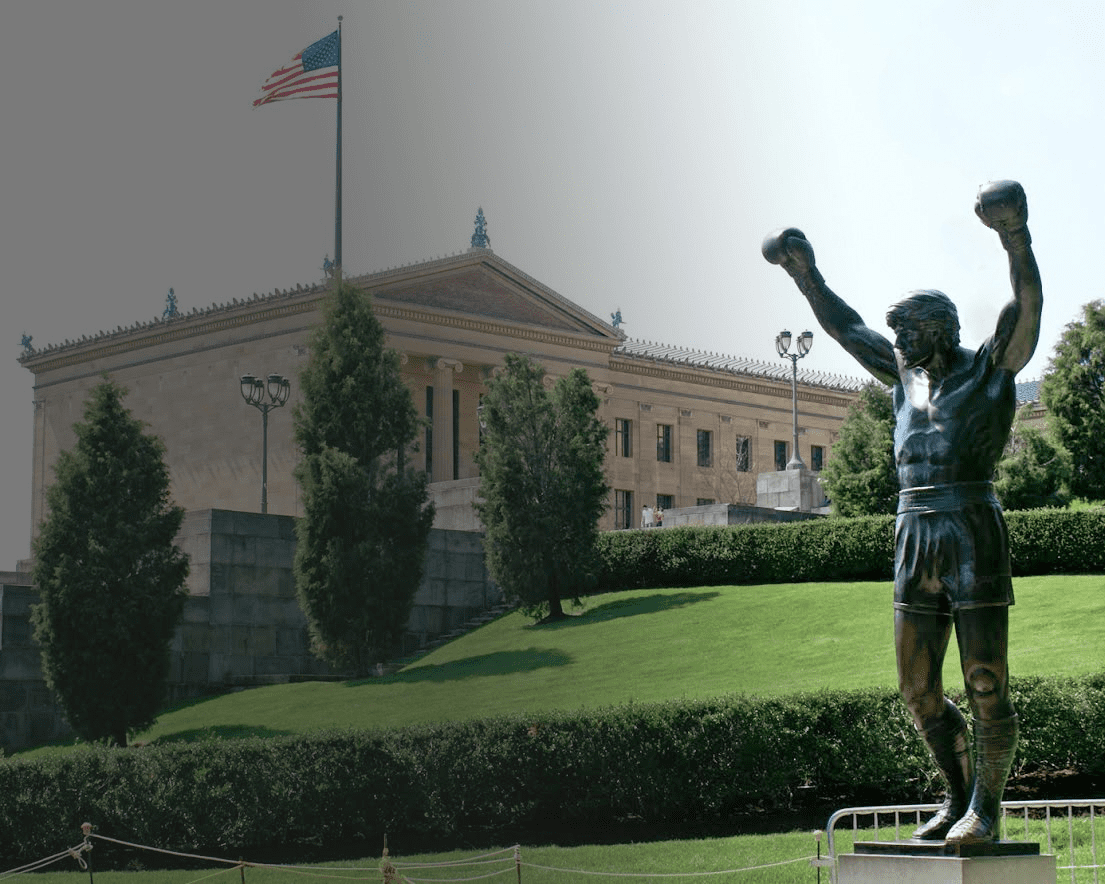

You cannot discuss this institution without mentioning its most popular external feature: the 72 stone steps of the east entrance. Before 1976, they were merely a grand staircase. But everything changed with the movie “Rocky.” The scene where the underdog boxer Rocky Balboa ascends these steps to a dramatic score became a worldwide symbol of grit, victory, and the American Dream.

This cinematic moment transformed the location into a global tourist landmark, instantly recognizable as the “Rocky Steps.” Climbing them has become a sort of pilgrimage for millions of visitors who strive to replicate Stallone’s victorious pose at the top, enjoying the panoramic view of the Parkway and City Hall. Even the bronze Rocky statue, which started as a movie prop, now permanently stands at the base, affirming the unique connection between high art and pop culture.

The Grand Renovation

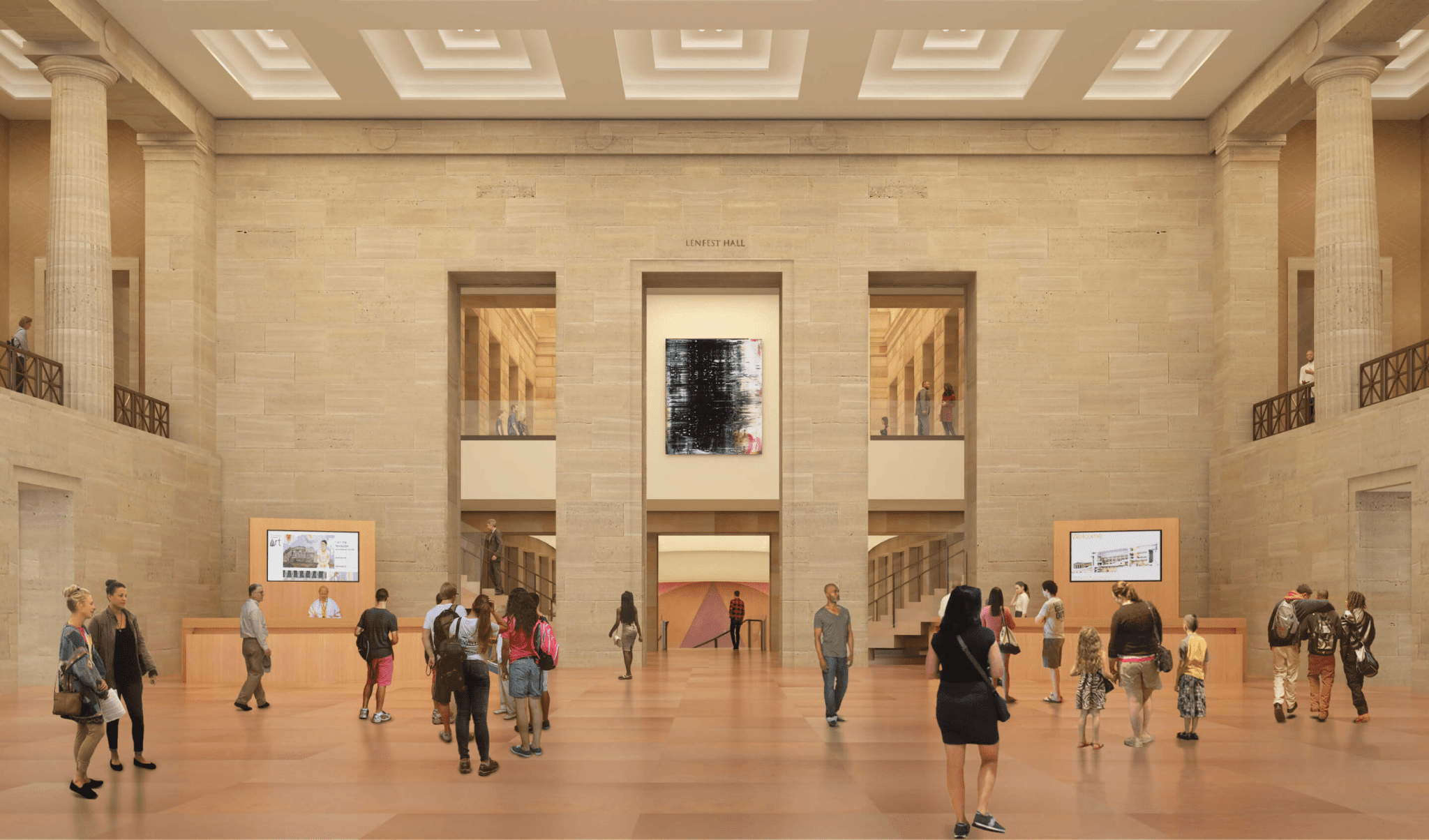

In the 21st century, the museum embarked on a massive interior “Core Project,” designed by the celebrated architect Frank Gehry. Rather than the external radicalism typical of his style, Gehry focused on “unclogging the arteries” of the old building.

The project, costing over $233 million, aimed to restore historic spaces that had been used as storage for years and to improve accessibility. Notably, the Vaulted Walkway, spanning 640 feet (about 195 meters), was reopened, and the Williams Forum—a new public space connected by a monumental curving staircase—was created. Gehry paid meticulous respect to the original 1928 materials, using the same golden-beige Kasota limestone for new elements, emphasizing a “seamless” transition between past and present.

The Museum Complex

The Museum of Art is not limited to just the main building on the hill. Its influence extends to several additional branches that collectively form a powerful art complex.

- The Rodin Museum. Located nearby, it holds the largest collection of works by sculptor Auguste Rodin outside of Paris. The collection was bequeathed to the city by film and theater magnate Jules Mastbaum.

- The Perelman Building. An elegant Art Deco structure that functions as a center for the collections of prints, photographs, and contemporary decorative arts, as well as an administrative hub.

- Historic Houses. The institution’s purview also includes 18th-century historic estates, such as Mount Pleasant, which allows for the display of decorative arts in their original historical context.

Consequently, the Philadelphia Museum of Art remains a dynamic, multifaceted cultural organism that simultaneously honors its historical roots and boldly looks to the future, solidifying its status as one of the world’s most vital cultural institutions.